“HunXueEr”: The Essentialization of the Half-Chinese Identities in 21st Century China

Introduction

On June 6th, 2019, 16-year-old biracial free-skiing athlete Eileen Gu announced on social media platforms that she would be competing for China in the upcoming 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics Games. This announcement implies that as an American citizen born and raised in California, she has given up her U.S. citizenship and gained naturalized Chinese citizenship. In writing, she said, “Through skiing, I hope to unite people, promote common understanding, create communication, and forge friendships between nations” with the emojis of American and Chinese flags at the end (Gu 2019). With two gold and a silver medal in hand for China in the 2022 Winter Olympics, Gu instantaneously gained Chinese governmental recognition and nationwide support. Gu’s identity as a “混血儿” (Hun Xue Er, mixed-blood kid) also stimulated many discussions regarding half-Chinese people’s belonging in Chinese society. Many netizens argue that non-Chinese-citizen half-Chinese people like Gu are all welcome back to their homeland, China (RenWu). However, the reality of many other half-Chinese people born and raised in China does not tell the same – those with darker skin are particularly treated with xenophobia as they are seen as the exceptions of a “yellow skin” bodily Chinese identity (Chang 577).

Because of the diversity of complexion, race, citizenship, and other factors, within the half-Chinese community, it is unjust to rely on representations that imply homogeneity. Yet, in China, the term HunXueEr is used by citizens to refer to all half-Chinese or mixed-race people without a doubt. In my paper, I argue that HunXueEr is a term that essentializes half-Chinese people’s identity and experience within a monoracial Han-Chinese-nationalist paradigm. I will first introduce the term’s literal and colloquial meaning and usage. Then I will discuss the racial formation in China, which is the underlying factor of privileges and discrimination. I will use three different social media case studies to support my argument – Beijing-raised half-Chinese half-Black woman Eden Guo, beloved half-Chinese half-white athlete Eileen Gu, and lastly, Russian vlogger Natasha, her Chinese husband, and their mixed-race child. With my examples, I will present HunXueEr’s complex senses of belonging and how they are challenged by the racial hierarchy in modern China, the static monoracial Chinese nationalism, and the everchanging Chinese foreign affairs agenda.

With limited literature centered on mixed-race people and experience in the Global South, this paper contributes to debates on racism from the perspective of those based in China. As a relatively new organization, Critical Mixed Race Studies Association (CMRS) was created in 2010 with the first issue of the Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies published in 2011 (Daniel 1). While Mixed Race Theory focuses on highlighting multiracial experiences, Critical Mixed Race Theory encompasses the intersectionality and fluidity of racial identity and calls to critically reflect on those identities and experiences (Clayton 36). CMRS also challenges race as a social construct since it pushes its audience to reconsider the term “mixed-race”. The use of CMRS in this research can explore mixedness in China with an intersectional perspective including race, gender, nationalism, etc. In this paper, I question the term HunXueEr in an effort to encourage Chinese speakers to adopt more inclusive terminologies and rethink their perception of the biological and socially constructed nature of “mixedness” in China. With the majority of the writings being oriented toward mixed-race communities in the West, I hope to contribute to an often omitted angle that examines mixed-race experiences in post-colonial societies. I also hope to challenge the essentialization of mixed-race identities in China and how they are reduced to a homogenous body of Han-Chinese people.

Upholding a firm belief that race is a social construct, I still recognize that it is an important classification that profoundly influences the social and political formation of the world. Multiple terminologies that express similar meanings in both academic and common dialogues, such as “mixed-blood”, “multiracial”, “hapa”, etc, have emerged throughout history. However, many of them are created on the basis of biological fallacy or colonial history. Since human races are scientifically proven to withhold 0.01% DNA differences and no genetic basis, the concept of “mixing” races is ambiguous (Duello 232). Despite similar terms’ limitations to express “mixedness”, it is also wrong to identify multiracial people with only one race as many Chinese identification documents do. Among mixed-race communities, there is a clear tendency to adopt the term “mixed-race” as self-identification in social contexts (Aspinall 6). With the contestability of race-mixing in mind, in this paper, I will be using the terms “mixed-race” and “half-Chinese” exclusively to avoid confusion and other identifications that imply discriminatory intent. To further define those terms, I refer to people whose biological parents identify as contrasting racial groups and those with part Chinese racial lineage respectively.

Additionally, in this paper, I will be only using Mandarin Chinese terminologies written in Simplified Chinese characters. To provide a pleasant reading experience for non-Chinese speakers, I have introduced Mandarin terminologies in such a format for their first appearances: “Simplified Chinese form”, (PinYin spelling, English meaning). For their later appearances, I will refer to them using their Romanized PinYin spelling in italic. Chinese phrases and quotes are also followed by my personal translation in parentheses.

Racial Formation in Post-Colonial China

The array of privileges and discrimination that half-Chinese people experience is influenced by the racial formation specific to post-colonial China and its agenda to promote ethnocentric nationalism among its citizens. The common belief of the Chinese race's origin can trace back to ancient mythologies about the creation of the Earth. In ancient Chinese literature and legends, the mystical figures “炎帝” (YanDi, flame emperor) and “黄帝” (HuangDi, yellow emperor) are regarded as the “始祖” (ShiZu, ancestors of the start) of Han Chinese people (Li). They formed the 华夏 (HuaXia) tribe, which is the preceding name for the Han ethnicity (Li). It was only after the creation of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 220 A.D.), in what is now East and Central China, that people started identifying as Han (Zhao et al. 1). Similarly, residents of the 中原 (ZhongYuan, Central Plains region) self-identified as the Tang people during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 A.D.) (Tang dynasty). In the late Qing Dynasty, politician Liang Qichao proposed the political ideology of “中华民族” (ZhongHuaMinZu, Chinese nation) (Zhao 45).

After undergoing decades of colonialism and civil war, the government felt the need to create a hegemonic Chinese identity to unite all 540 million citizens upon the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. Having a shared Chinese identity is considered to more easily mobilize the grand population to resist imperialism and create common sentiments. As a result, all people are considered to be of the Chinese race, yet, are categorized into 56 ethnicities institutionally. The strategy still holds true today with China’s evergrowing, what is now 1.4 billion, population (Chen). During Chairman Xi Jin Ping’s visit to Tibet in 2021, he stated, “我们56个民族是中华民族共同体 (Our 56 ethnic groups are of the shared ZhongHuaMinZu community)” (Song). On every Chinese citizen’s national identification card, ethnicity is one of the classifications in addition to name, gender, blood type, and address. Limitations withstand since individuals can only put one ethnicity, preventing people of mixed- ethnic/racial backgrounds from claiming multiethnicity (Clayton 39). For non-Chinese foreigners who gained Chinese citizenship, regardless of their ethnicities, it is written as “外国血统 (foreign origin/lineage)” ([If a foreigner becomes a Chinese citizen, what should be filled in the "ethnicity" column on his ID card?]). However, if the original nationality/ethnicity of the naturalized individual has a corresponding ethnic group in China, they can fill in the related ethnic group. Similarly, if one of the individual’s parents is of Chinese origin, they will follow that parent’s ethnic identification.

Chinese racial identity politics is also present in popular culture as similar nationalist terms emerged in songs and other media formats. The song “龙的传人 (Descendents of the Dragon)” was first written in 1978, but popularized in the 2000s by Chinese American singer Wang Leehom. In 2009, "Descendants of the Dragon" was selected as one of the 100 patriotic songs recommended by the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party (Zhu). The song is widespread among all Chinese people across the diaspora, with lyrics such as “黑眼睛 黑头发 黄皮肤, 永永远远是龙的传人 (black eyes, black hair, yellow skin, forever Descendants of the Dragon)”. These lyrics emphasize a shared set of Chinese physical features and exclude people who cannot be bodily defined as Chinese according to these standards, such as HunXueEr who often possess assorted sets of physical features.

Social Darwinism was one of the major influences on China’s racial hierarchy formation: a theory that upholds “survival of the fittest” to justify racism (Xu 182). Prominent Chinese thinkers and reformists of the same time such as Liang Qichao and Kang Youwei adopted such ideals in their discussion of race. They suggested a racial hierarchy that places the white and Chinese on top as the fittest and the Black at the bottom with the most defects. In the late 19th Century, British scholar Sir Francis Galton created eugenics, aiming at improving the human race by discarding racial defects (Gillham 1). Revolutionaries believed in the preservation of the Han Chinese race for their people’s self-determination in the face of Western colonialism and Manchu occupation (Chung 797). The purity of a Chinese race is seen as crucial for national survival and success. Within the Chinese race, Liang and Kang advocated for earlier reproductive age, better prenatal care, and a higher rate of women's education as techniques for higher reproductive success (Chung 797). While Kang promoted interracial marriage between white and Chinese people to better “whiten” the Chinese people, interracial marriage between Black and Chinese people is supposed to eventually eliminate the Black race (Chung 797). Other eugenic plans include the sterilization of Black people (Cheng 563). As much as China’s racial formation is shaped by its domestic politics and profound history, it is also largely influenced by Western thoughts and colonialism.

Social Darwinist ideas on race still remain influential in modern China as Black people are seen as the “primitive and inferior Other” (Cheng 574). China positions itself as the savior in the Sino-African relationship – providing economic aid, humanitarian assistance, and trade opportunities. Consequently, such a mindset is reflected in common terminologies as China’s interaction with Africa is often described as “援非” (YuanFei, aid Africa). Within China, African business workers find themselves in a “de facto apartheid” where they are intentionally separated from others (Cheng 565). As I will explore further in this paper, because of China’s ethnocentric nationalism, the idea of “racial purity” is highly valued to prove loyalty to the nation and interracial marriages between Chinese and Africans are rather seen as “racial invasion” (Cheng 567).

Within modern China, there is also a common belief that racism only exists in Western countries since Chinese people were once the target of colonialism and are still discriminated against in the West. The tense Sino-US relationship also fuels the Chinese government’s intention to push an anti-America agenda. Discussions on race-related foreign affairs are often used to portray a strong contrast between China, where supposedly all 56 different ethnicities live harmoniously, and the United States, where People of Color are constantly discriminated against. The end goal is to present China as the winner, therefore, boost Chinese national sentiments through the degradation of living experiences in America and other countries. Chinese people often turn blind to their own racism fundamentally because of the lack of education on race and racial justice. As seen in later paragraphs, many anti-Blackness arguments are uneducated stereotypes and knowledge of race-mixing is biologically incorrect.

What is HunXueEr

In Chinese, the term 混血儿 (hùn xuè ér) literally means “mixed blood kid” and is used to refer to mixed-race people. On the major Chinese search engine and digital encyclopedia, Baidu, it is defined as a biological term meaning “不同人种父母的后代 (offspring of parents of different races)'' (混血儿 [Hun Xue Er]). Colloquially, Chinese speakers use the term HunXueEr to name all multiracial people, primarily the ones with part Chinese ancestry. Both adjectives “混血” (HunXue, mixed-blood) and “杂交” (ZaJiao, hybridized) can be applied to all forms of human and non-human “hybrid” beings. However, HunXue is more commonly used for humans while the extended noun from ZaJiao, “杂种” (ZaZhong, bastard) is explicitly discriminatory. Because of the fluidity of the term HunXue and the kinship basis of blood lineage, HunXue can be also used to describe individuals with mixed backgrounds from socially-differentiated groups such as “南方人” (NanFangRen, Southerner) and “北方人” (BeiFangRen, Northerner). A common integration of the words would be “南北混血” (NanBeiHunXue, South North mixed- blood) ([What is it like to be a "HunXueEr" of the North and the South?]).

The linguistic use of “blood” is not simply a biological misconception, but rather has greater implications for a national identity built upon a monoracial Chinese blood lineage. As a Chinese idiom goes, “血浓于水 (Blood is thicker than water)”, blood is commonly used as a metaphor for relatedness and kinship. The term “血缘” (Xue Yuan) is literally translated as “blood fate” and has become the widely recognized Chinese term for consanguinity. Consequently, race and ethnicity in China are also believed to be passed down through blood and kinship. Likewise, as found in research conducted within the mixed-race community itself, mixed-race people often explain their identity through a heteronormative kinship narrative in which they “inherit ‘national origin’ ‘through blood’” (Paragg 285). Nonetheless, it is important to recognize the lack of education on the socially constructed nature of race in China since it is scientifically proven that there is no genetic or bloodwork basis for race (Duello 232).

It is also important to note that although the dominant ethnicity in China is Han Chinese (91.11%), the belief that the Han ethnicity has stayed monoracial throughout history is debatable (Chen). Throughout pre-modern China’s thousands of years of history, the borders and occupied regions were constantly changing. Ancient China was also interacting with the rest of the world through trade exemplified by the ancient Eurasian trade route “丝绸之路 (Silk Road)”. Inter-ethnic and inter-racial marriages were initiated to promote political alliances among different dynasties and emperors. Because of ancient China’s active role in the world, the monoraciality of the Han ethnicity is contested. Additionally, the Han identity was not created until 202 BC and was originally geography-based. Although not commonly accepted, to an extent, one could argue that the vast majority of Chinese people are not strictly monoracial. Clayton also argues in his writing that Han Chineseness is a hybrid imagined identity that is the consequence of thousands of years of intermarriages among various ethnic groups (Clayton 42). Nonetheless, after a series of wars, ethnic cleansing, and assimilation, racial/ethnic differences are underestimated to instead emphasize a shared Chinese cultural experience and racial identity. As a result, the current greater political climate undermines half-Chinese people’s identity complexity in order to further promote homogeneous Han Chinese nationalism.

Being Half-Black Half-Chinese: Eden Guo

I have felt that I am different from other people because no matter where I go, as long as it is in a public place, whenever anyone sees me, they will take a second look. They would want to touch my hair or ask if I could speak Mandarin.

– Eden Guo (Being black and mixed-race in China: Gen 跟 China)

Longstanding anti-Blackness in China puts half-Black half-Chinese people in an identity dilemma where they do not feel welcomed by people that they consider as their own. The objective of keeping “racial purity” in order to construct higher nationalist sentiment excludes those unwanted races from being identified as Chinese (Clayton 36). While China is sensitive towards racism against its own people because of a traumatic colonized past, Chinese people still are largely insensitive towards racism against other races. China’s growing global development levels itself as one of the most powerful countries in the world, justifying its racism toward Black people as they are seen as the inferior primitive race. Additionally, China’s tremendous amount of aid to Africa not only enables a savior complex for its citizens, some even oppose the government’s support to Africa as it is feeding “uncultured Africa with the results of our efforts” (Chang 564). Such racist mindsets are thus reflected in the mistreatment of half-Black half- Chinese people, evicting them from ZhongHuaMinZu (the Chinese nation).

As introduced in a VICE Asia video “Being Black And Mixed-Race in China”, Eden Guo is a half-African half-Chinese young woman who was born in Uganda and raised in China’s capital, Beijing. Her Chinese father worked as a businessman and met her Ugandan mother through work, thus she was born in Uganda (Being black and mixed-race in China: Gen 跟 China). The family returned to China when she was two years old for better educational resources. However, her parents divorced when she was only around 4-5 years old and she never met her mother again. Guo’s upbringing is no different than any other monoracial Chinese girl growing up in China. Even though Guo has always identified herself as a “typical Beijing girl”, other monoracial Chinese people do not see her that way because of her appearance (Being black and mixed-race in China: Gen 跟 China). Guo has mixed features such as curly hair and a darker skin complexion, which do not belong to the “Descendants of Dragon” set of features. Even coming from Guo herself, she had always felt that she was different from others because of the extra attention that she received in public spaces (Being black and mixed-race in China: Gen 跟 China).

Similarly, other half-African half-Chinese people struggle with self-identification and a sense of belonging because of the Chinese public’s denial of their claim to Chineseness. In a 2009 talent show entitled “加油!东方天使 (Go! Oriental Angel)”, half-African half-Chinese young woman Lou Jing represented Shanghai to compete against other Chinese young women (Lim). The internet was flooded with comments that denied her identity as a Chinese person, asserting that she is not a “real Chinese” who “never should’ve been born” and should “get out of China” (Growing Up Black In China). When the people learned that her father was an African American man who she had never met, racist comments regarding Lou’s family and identity overpowered compliments for her talents.

The influx of hurtful comments toward half-African half-Chinese people is led by anti-Blackness in China. Even though economic activities between China and African countries have significantly increased since the late 1990s, discrimination against African migrants in China is nowhere near settled. Particularly, Black men are often stigmatized as sexual predators who would have relationships and offspring with Chinese women but eventually abandon them (Huang). Others believe that Black men have brought and transmitted sexual diseases such as HIV in China (Being black and mixed-race in China: Gen 跟 China). Although the relationship between a Black man and a Chinese woman is seen as forbidden, relationships between a Chinese man and an African woman are rather seen as triumphant. Children of interracial African-Chinese families are therefore considered unaccepted and incompetent. As one comment stated, “African blacks are an inferior race. Children of Chinese and African blacks should be regarded as mixed but inferior race” (Chang 567). It has even become a common joke that half-African children do not have fathers. The normalization of these jokes shows the Chinese public’s insensitivity towards and the lack of education regarding racism against other races. These harmful stereotypes discriminate against half-Black half-Chinese people and reject their formation of familial and national identity.

Half-Black HunXueEr are constantly under the racial gaze in verbal form like being questioned “What are you” and “Do you speak Mandarin”, or in physical form like touching one’s afro hair in Guo’s instance (Being black and mixed-race in China: Gen 跟 China). In these situations, they are always Othered as foreigners alongside their parents by monoracial Chinese people. The advancement of a rigid “yellow skin” Han Chinese nationalist identity results in the marginalization of HunXueEr who have more apparent physical differences. Other psychological side-effects include the sense of “racial homelessness” and “emotional distress” (Jones and Rogers 2). The term HunXueEr’s failure to capture the complexity of identities and differing degrees of discrimination within the half-Chinese community is even more apparent in comparison to later examples of half-white half-Chinese experiences.

Being Half-white Half-Chinese: Eileen Gu

I definitely feel as though I am just as American as I am Chinese. I am American when I am in the US, and I am Chinese when I am in China... I don't feel as though I'm, taking advantage of one or the other, because both have actually been incredibly supportive of me and continue to be supportive of me, because they understand that my mission is to use sport as a force for unity, to use it as a form to foster interconnection between countries and not use it as a divisive force.

– Eileen Gu (Reporters press Eileen Gu over her citizenship. see her response)

Since freestyle skiing athlete Eileen Gu announced her decision to represent China in international competitions in 2019, the Chinese government and commoners have entrusted her with high hopes – both to win medals and to inspire positive national sentiments (Cao and Pu 209). Gu took home 2 golds and a bronze during the 2021 Winter X Games in Aspen, then 2 golds and a silver during the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics (Cao and Pu 209). Ever since then, she has received unanimous praise for her distinguished achievement in the sport as well as her other favorable qualities, given the nickname of “Snow Princess” (Saito and Zhou). With interviews, brand deals, and business contracts overflowing, Gu became the perfect poster child for China to foster a sense of racial inclusivity and unity. According to Dutch historian Frank Dikötter, the discourse of race in China since the founding of the PRC orients around nationality and the promotion of cultural diversity (Dikötter 191-196). Gu’s escalating support is anything but coincidental: not only is she athletic, but she is also great at traditional testing as she gained 1580/1600 on SAT (positive academic performance is equated by Chinese people to prove success in life); she is committed to her studies since she will immediately return to Stanford after the Olympics; she is considered very beautiful and became the front face for a handful of global brands, and as a HunXueEr, she is well versed in the Chinese language and culture since she returns to China every summer.

Gu has inevitably succeeded in being the epitome of the “中国梦” (ZhongGuoMeng, Chinese dream), a nationalist slogan defined by Xi Jinping as “中华民族伟大复兴 (the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation)” (Allison). Because of the intensely controlled media outlet in China, the major networks can only produce content that is in the interest of the Party. Eileen Gu’s endorsement by the government is strategic to promote national unity, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country. In 2022, China’s national sentiments among its citizens were boosted as Beijing became the first city to have held both the Summer and Winter Olympics in the world. Baidu published data from the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, showing a 6 times increase in popularity from the previous games (Ding). Gu’s example is also particularly useful in proving how the naturalization of athletes could supposedly dissolve exclusive nationalism (Cao and Pu 209). During the current heightened political tension between China and the U.S., Gu’s naturalized status digs deeper motives than simply returning to one’s heritage. Because of the Chinese government’s framing of a global competition between China and America, Chinese citizens find pride in winning against America in all aspects of society. Gu's unique identity as a half-white half-Chinese extinguished athlete who chose to compete for China becomes the perfect model and an opportune case for the Chinese government to showcase its dominance over America.

Despite all this, Eileen Gu’s citizenship status remains an unsolved mystery to the public. Since China does not legally allow dual citizenship, presumably San Francisco-born-and-raised Gu would have to give up her American citizenship (Nationality Law of the People's Republic of China). Meanwhile, based on domestic policy, the United States Internal Service publishes a Quarterly Publication of Individuals, Who Have Chosen to Expatriate in the Federal Register which includes names of the individuals who have records of the loss of American citizenship during the past quarter (The Federal Register). However, Gu’s name is nowhere to be found in the lists, stirring debates regarding her citizenship status. During interviews, Gu only finds ways to circle around the question and shift her focus on promoting unity through skiing between the two countries (Reporters press Eileen Gu over her citizenship. see her response). During one of the interviews, she responded to questions regarding her citizenship status by saying “I am American when I am in the US, and I am Chinese when I am in China...” (Reporters press Eileen Gu over her citizenship. see her response). While Gu aims at maintaining the duality and intersectionality of her cultural and racial identity, as previously mentioned, she would have had to choose one ethnicity on her ID card like any other Chinese citizen.

Other half-white-American half-Chinese people have rather expressed dissimilar feelings regarding the wide acceptance of Eileen Gu in China. Audrey Siegel, a video editor who identifies as Chinese and white-American HunXue stated during the VICE Asia interview that, more Chinese people started paying attention to the mixed-race community because of Eileen Gu, yet “at the same time, [she is] very envious that Chinese people accept [Eileen Gu] as Chinese.” Siegel revealed that she was treated with privilege growing up in a dance school possibly because others thought “[she] was cute” for looking “white, round, and fat”. She acknowledges that such experience could be “related to [her] identity as a mixed-race” (Being black and mixed-race in China: Gen 跟 China). In spite of the privileges, she still constantly faces the struggle of not being recognized as “Chinese enough” by other monoracial Chinese citizens (Being black and mixed-race in China: Gen 跟 China). Both Siegel and Gu are HunXueEr who obviously don’t share the racialized “Descendants of Dragon” physical features since they have pale skin, brunette hair, and non-black eyes. However, they are treated with an inconsistent sense of community and recognition of Chineseness by monoracial Chinese people. The disconnect between the conventional bodily requirements to prove Chineseness and the tremendous sense of comradery shared among Eileen Gu and non-mixed-race Chinese citizens is apparent.

Being a Multiracial Family in China

“见见我家混血萌娃,俄语不会说,中文一句不落..... (Meet my cute HunXue baby who can't speak Russian, but won’t miss a sentence of Chinese...)” (Natasha, Natasha’s Family)

So far, by juxtaposing the examples of half-Black and half-white HunXueEr, I presented the diverging spectrum of acceptance and exclusion that half-Chinese people experience because of their other half racial identity. In this section, I aim to show how multiracial families in China conform to the monoracial Han-Chinese nationalist paradigm by socializing their half-Chinese children to abandon the other parts of their racial identity. Therefore, HunXueEr have in turn homogenized themselves in order to gain social and economic capital. Specifically, I will focus on a Russian mother and vlogger Natasha and her multiracial family.

Natasha has a channel named “娜塔莎一家 (Natasha’s Family)” on China’s major video site Bilibili. Her channel description reads, “我在中国学习中医,被中国男人拐跑了 (I am studying Chinese medicine in China, was lured by a Chinese man)” (Natasha's Family). Her top video on Bilibili is entitled “让我滚出中国?凭什么!! (Asking Me to Get Out of China? On What Basis!!)” with 2.66 million views (Natasha’s Family). It addresses her identity as a foreign wife and the bigotry attacks that she has received such as “get out of my country” and “stop snatching Chinese men from us” (Natasha’s Family). She addresses rumors and speculations that she got married to a Chinese man to be a “gold digger”. In the comment section, the most liked comment by a hundred thousand people says “哎,娜塔莎,骂你的可能不是中国人,有人故意在网络挑事的 (Sigh, Natasha, the one who discriminated against you may not be Chinese, there are people who deliberately provoke trouble on the Internet)”. It implies that Chinese citizens are all very open to foreigners so it is only possible that people from other countries intentionally send hate to degrade Chinese netizens’ integrity. In reality, as shown in previous paragraphs regarding half-Black HunXueEr, not all foreigners are welcomed in China.

Her other videos promote similar Chinese nationalist sentiments such that her second top entitled “我是中国人,为啥要逼我学俄语 (I Am Chinese, Why Force Me to Study Russian)” with 2.11 million views (Natasha’s Family). In this video, she records a casual conversation with her own mixed-race son David and her full-Russian nephew Artem. While David is still too young to speak fluently, when asked about their Russian language level, Artem responded in Chinese: “I can’t”, “It’s too difficult”, and “[I already forgot] because I am Chinese” (Natasha’s Family). One of the top comments on this video reads,

“学学学,我们支持,不学米国搞文化清洗那一套,孩子学会的语言越多越好,认同中国人身份的话,将来用学到的知识帮助祖国建设就行了,比如中俄有好交流

(Learn, learn, learn, we support it, don’t be like the cultural cleansing in America, the more languages the children learn, the better. If they identify with the Chinese identity, they can use the knowledge they have learned to help with the construction of our motherland in the future, for example, the friendly exchanges between China and Russia.)”

It is obvious to read from Natasha’s titles that she is promoting Chinese cultural and racial supremacy to her own son and younger relatives through conversations. As a Russian woman living in China, Natasha needs to understand what matters are favored by Chinese netizens and consequently create headlines that are attractive to the public. In her context in a major Chinese-only platform, it means appealing to the Chinese people’s nationalism which is manifested as her degradation of her own country of origin. She uses the fact that her son is more accepting of Chinese culture and language than Russian’s to appeal to her Chinese audience’s nationalist sentiment. Arguably she upholds such morals for gaining economic capital, at the same time, the messages of these videos are communicating to the younger generation in her family that China and the Chinese race are superior to the others in the world. Natasha as a mother, an aunt, and a vlogger with a big following possesses great power in influencing how her younger audiences understand their own race and those around them. In these scenarios, Natasha’s son didn’t have a chance to be equally educated on both parts of his identity because of his mother’s deliberate choice to emphasize the Chinese side.

Based on my previous examples of HunXueEr Audrey Siegel and Eden Guo feeling unrecognized as Chinese despite their fluency in the language and upbringing in the country, one could imagine that Natasha’s son will still experience similar racial gaze that Others him despite his mother’s strong effort to conceal his Russian identity. This serves as an example that regardless of one’s active efforts to assimilate into the Chinese nation, it is largely dependent on the monoracial Chinese people’s reaction to determine whether or not you are “Chinese enough”. It is also an example of the various factors that influence HunXueEr’s perception of their own racial identity: where do you grow up, what do your parents teach you about yourself, how much do you understand both of your parents’ racial identity, etc.

Conclusion: Essentialization

Stemming from the word “essence”, the philosophical concept of essentialism originally implies that all entities have an inherent nature. In anthropology, essentialization is adopted to refer to the claim that all people of a specific identity or group share fixed inherited traits and characteristics. The process of essentialization reduces the complexity and diversity of people’s identities to a homogenized representation.

From the examples above, the intersectionality of identities is pronounced with factors such as skin complexion, citizenship, social status, occupation, etc. In the first instance, dark-skinned HunXueEr such as Eden Guo are often discriminated against because of anti-Blackness racism in China; Eileen Gu is endorsed and popularized by the Chinese government to promote positive and inclusive national sentiments, and Natasha’s family commercializes their children’s Eurasian identity and emphasize Chinese nationalism for Chinese recognition and financial benefits. All of them experience disconnection with or the need to claim “Chineseness” forced by other monoracial Chinese citizens. China’s push for a monoracial Han-based national identity contradicts its goal to present itself as an inclusive and open nation. Given the constantly shifting Sino-American political conditions, HunXueEr who possesses American origin or citizenship’s experience in China is not only defined by their race but also by the current relationship between the two countries.

Rather than emphasizing the fluidity of HunXue identities, the term HunXueEr essentializes all mixed-race people’s intersectional individuality in China. Additionally, Chinese domestic policies restrict HunXueEr’s self racial-identification by enforcing a singular ethnic association in formal government documents. The broader nationalist social environment also pressures them (at times their parents) to reject their non-Chinese sides of identity. Monoracist policies and beliefs systemically oppress people of mixed-race backgrounds as they do not fit into monoracial categorizations or identifications. While it should be up to the mixed-race individuals to judge their connection to their respective racial identities, monoracism is manifested in the acts of policing how mixed-race people should identify themselves and determining the authenticity of Chineseness.

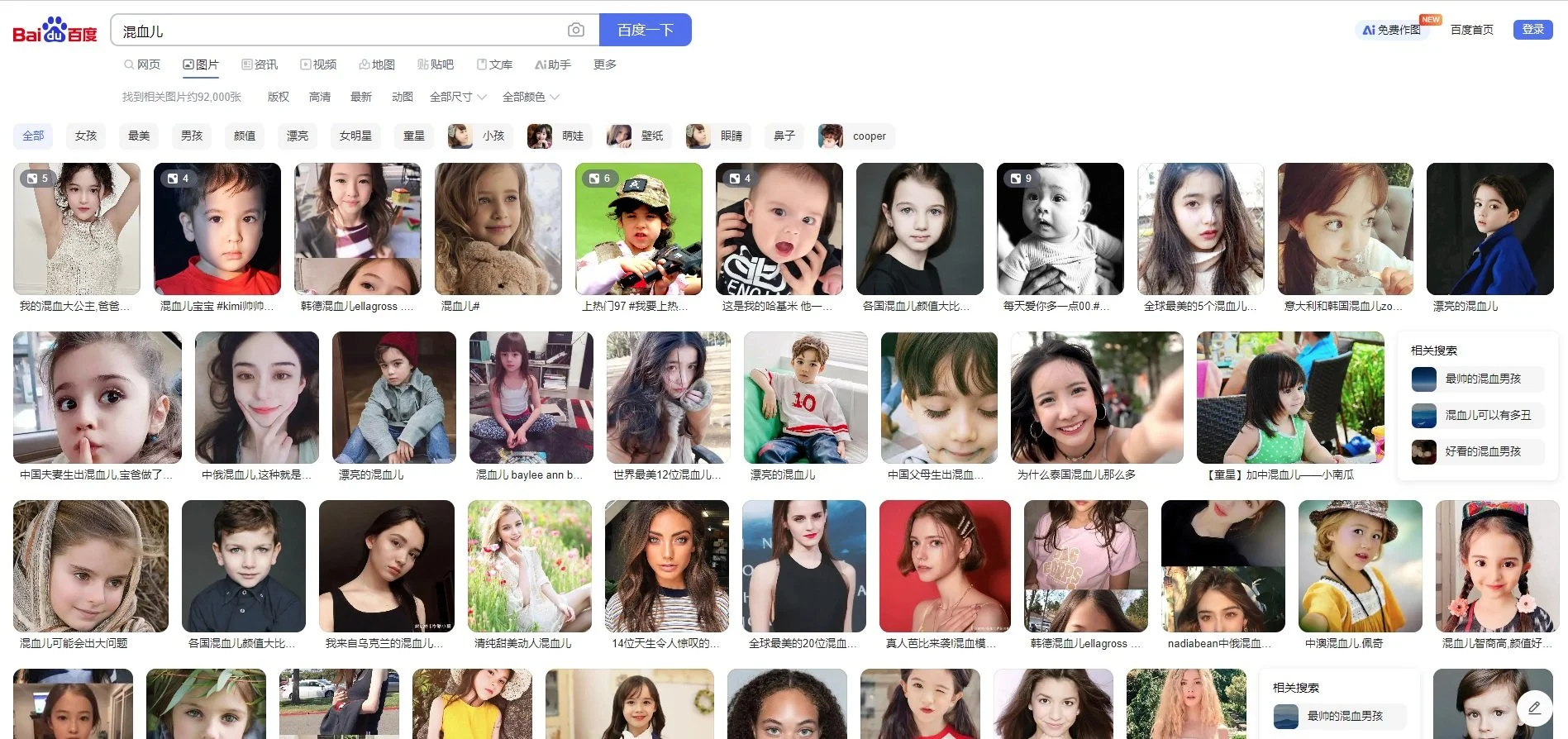

Yet, unlike mixed-race in English which directly points to racial identity, HunXue, “mixed-blood” possess the flexibility to refer to all hybrid beings. In a way, it challenges the rigid idea of race in spite of the biological misconception of bloodwork. Still, having a singular word for such a diverse demographic can lead to stereotypes and other generalized assumptions being easily applied to refer to the whole group. When one searches the term HunXueEr on Baidu, the page is dominated by images of Eurasian adults and children. There is also a clear imbalance in mixed-race representation in China with monopolizing discussions on half-white experiences.

As suggested by Cathryn Clayton, there needs to be “conceptual frameworks that can do justice to both the specificity and elasticity of the blood metaphor” because of its duality in expressing national and racial origin (Clayton 46). Scholars who adopt Critical Mixed Race Theory should aim at deconstructing the rigid terminologies that constrain self-expression and intersectionality. In hopes of doing so, the world beyond academics and activism can also reexamine race as a social construct. Changing commonly used daily terms is a more accessible method to reach those who might not have adequate access to education.

Although I only included three case studies, I do not wish to undermine the varying levels of discrimination or privileges that HunXueEr of other backgrounds experience. By conducting a more comprehensive study, one can better understand how HunXueEr’s personal experiences can reflect China’s domestic and foreign politics. As China continues to grow and become one of the strongest world powers, it should also dismantle its rigid racial structure and monoracial nationalist policies to keep its promises of an inclusive community.